writing-prompt-s:

Temples are built for gods. Knowing this a farmer builds a small temple to see what kind of god turns up.

Arepo built a temple in his field, a humble thing, some stones stacked up to make a cairn, and two days later a god moved in.

“Hope you’re a harvest god,” Arepo said, and set up an altar and burnt two stalks of wheat. “It’d be nice, you know.” He looked down at the ash smeared on the stone, the rocks all laid askew, and coughed and scratched his head. “I know it’s not much,” he said, his straw hat in his hands. “But – I’ll do what I can. It’d be nice to think there’s a god looking after me.”

The next day he left a pair of figs, the day after that he spent ten minutes of his morning seated by the temple in prayer. On the third day, the god spoke up.

“You should go to a temple in the city,” the god said. Its voice was like the rustling of the wheat, like the squeaks of fieldmice running through the grass. “A real temple. A good one. Get some real gods to bless you. I’m no one much myself, but I might be able to put in a good word?” It plucked a leaf from a tree and sighed. “I mean, not to be rude. I like this temple. It’s cozy enough. The worship’s been nice. But you can’t honestly believe that any of this is going to bring you anything.”

“This is more than I was expecting when I built it,” Arepo said, laying down his scythe and lowering himself to the ground. “Tell me, what sort of god are you anyway?”

“I’m of the fallen leaves,” it said. “The worms that churn beneath the earth. The boundary of forest and of field. The first hint of frost before the first snow falls. The skin of an apple as it yields beneath your teeth. I’m a god of a dozen different nothings, scraps that lead to rot, momentary glimpses. A change in the air, and then it’s gone.”

The god heaved another sigh. “There’s no point in worship in that, not like War, or the Harvest, or the Storm. Save your prayers for the things beyond your control, good farmer. You’re so tiny in the world. So vulnerable. Best to pray to a greater thing than me.”

Arepo plucked a stalk of wheat and flattened it between his teeth. “I like this sort of worship fine,” he said. “So if you don’t mind, I think I’ll continue.”

“Do what you will,” said the god, and withdrew deeper into the stones. “But don’t say I never warned you otherwise.”

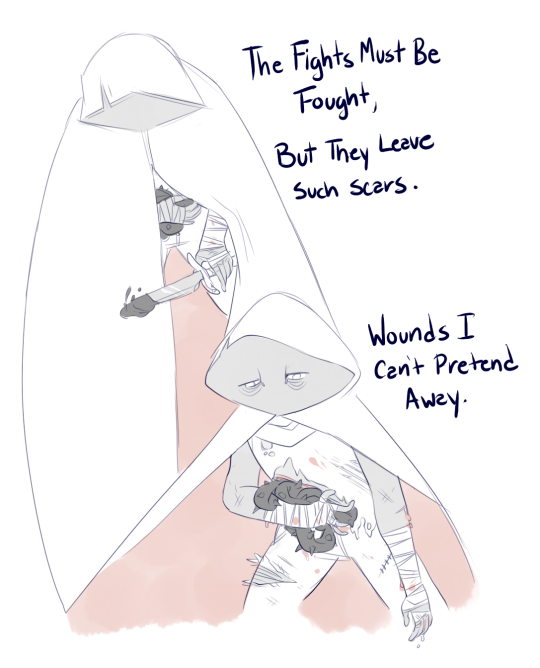

Arepo would say a prayer before the morning’s work, and he and the god contemplated the trees in silence. Days passed like that, and weeks, and then the Storm rolled in, black and bold and blustering. It flooded Arepo’s fields, shook the tiles from his roof, smote his olive tree and set it to cinder. The next day, Arepo and his sons walked among the wheat, salvaging what they could. The little temple had been strewn across the field, and so when the work was done for the day, Arepo gathered the stones and pieced them back together.

“Useless work,” the god whispered, but came creeping back inside the temple regardless. “There wasn’t a thing I could do to spare you this.”

“We’ll be fine,” Arepo said. “The storm’s blown over. We’ll rebuild. Don’t have much of an offering for today,” he said, and laid down some ruined wheat, “but I think I’ll shore up this thing’s foundations tomorrow, how about that?”

The god rattled around in the temple and sighed.

A year passed, and then another. The temple had layered walls of stones, a roof of woven twigs. Arepo’s neighbors chuckled as they passed it. Some of their children left fruit and flowers. And then the Harvest failed, the gods withdrew their bounty. In Arepo’s field the wheat sprouted thin and brittle. People wailed and tore their robes, slaughtered lambs and spilled their blood, looked upon the ground with haunted eyes and went to bed hungry. Arepo came and sat by the temple, the flowers wilted now, the fruit shriveled nubs, Arepo’s ribs showing through his chest, his hands still shaking, and murmured out a prayer.

“There is nothing here for you,” said the god, hudding in the dark. “There is nothing I can do. There is nothing to be done.” It shivered, and spat out its words. “What is this temple but another burden to you?”

“We -” Arepo said, and his voice wavered. “So it’s a lean year,” he said. “We’ve gone through this before, we’ll get through this again. So we’re hungry,” he said. “We’ve still got each other, don’t we? And a lot of people prayed to other gods, but it didn’t protect them from this. No,” he said, and shook his head, and laid down some shriveled weeds on the altar. “No, I think I like our arrangement fine.”

“There will come worse,” said the god, from the hollows of the stone. “And there will be nothing I can do to save you.”

The years passed. Arepo rested a wrinkled hand upon the temple of stone and some days spent an hour there, lost in contemplation with the god.

And one fateful day, from across the wine-dark seas, came War.

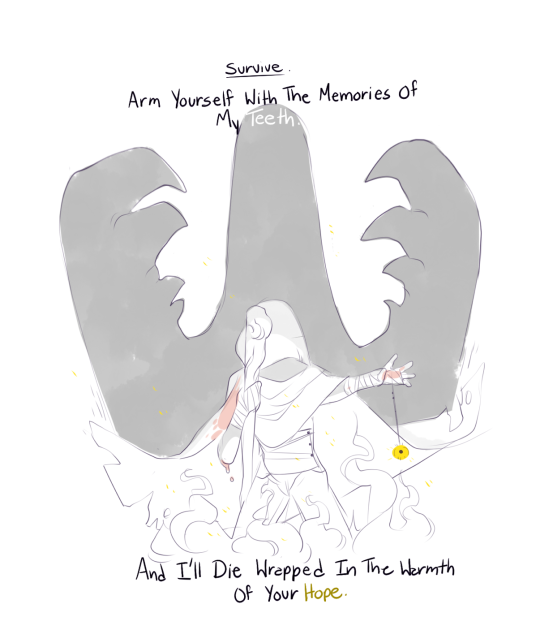

Arepo came stumbling to his temple now, his hand pressed against his gut, anointing the holy site with his blood. Behind him, his wheat fields burned, and the bones burned black in them. He came crawling on his knees to a temple of hewed stone, and the god rushed out to meet him.

“I could not save them,” said the god, its voice a low wail. “I am sorry. I am sorry. I am so so sorry.” The leaves fell burning from the trees, a soft slow rain of ash. “I have done nothing! All these years, and I have done nothing for you!”

“Shush,” Arepo said, tasting his own blood, his vision blurring. He propped himself up against the temple, forehead pressed against the stone in prayer. “Tell me,” he mumbled. “Tell me again. What sort of god are you?”

“I -” said the god, and reached out, cradling Arepo’s head, and closed its eyes and spoke.

“I’m of the fallen leaves,” it said, and conjured up the image of them. “The worms that churn beneath the

earth. The boundary of forest and of field. The first hint of frost

before the first snow falls. The skin of an apple as it yields beneath

your teeth.” Arepo’s lips parted in a smile.

“I am the god of a dozen different nothings,” it said. “The petals in bloom that lead to

rot, the momentary glimpses. A change in the air -” Its voice broke, and it wept. “Before it’s gone.”

“Beautiful,” Arepo said, his blood staining the stones, seeping into the earth. “All of them. They were all so beautiful.”

And as the fields burned and the smoke blotted out the sun, as men were trodden in the press and bloody War raged on, as the heavens let loose their wrath upon the earth, Arepo the sower lay down in his humble temple, his head sheltered by the stones, and returned home to his god.

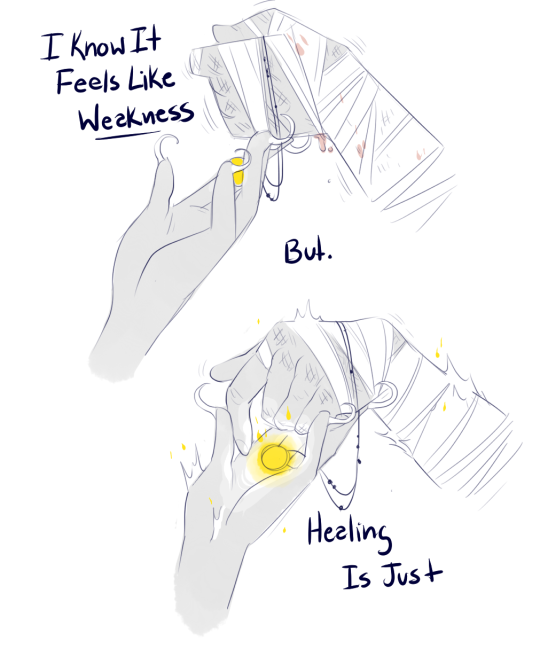

Sora found the temple with the bones within it, the roof falling in upon them.

“Oh, poor god,” she said, “With no-one to bury your last priest.” Then she paused, because she was from far away. “Or is this how the dead are honored here?” The god roused from its contemplation.

Sora startled, a little, because she had never before heard the voice of a god. “How can I honor him?” She asked.

“All right,” Sora said, and went to fetch her shovel.

“Wait,” the god said when she got back and began collecting the bones from among the broken twigs and fallen leaves. She laid them out on a roll of undyed wool, the only cloth she had. “Wait,” the god said, “I cannot do anything for you. I am not a god of anything useful.”

Sora sat back on her heels and looked at the altar to listen to the god.

“When the Storm came and destroyed his wheat, I could not save it,” the god said, “When the Harvest failed and he was hungry, I could not feed him. When War came,” the god’s voice faltered. “When War came, I could not protect him. He came bleeding from the battle to die in my arms.” Sora looked down again at the bones.

“I think you are the god of something very useful,” she said.

“What?” the god asked.

Sora carefully lifted the skull onto the cloth. “You are the god of Arepo.”